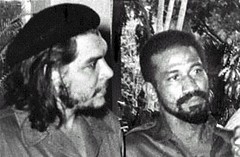

Che Guevara and Juan Almeida, leaders of the Cuban revolution. Guevara died in Bolivia in 1967 and Almeida passed on during September 2009.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

"We shall go to the sun of freedom or to death; and if we die, our cause will remain alive. Others will follow us."

—Augusto César Sandino

• Interview with Nicaraguan Rodolfo Romero,

internationalist fighter and founder member of the Sandinista National Liberation Front

Anneris Ivette Leyva

WHEN, in his eagerness to evoke them in the present, events of the past become elusive, Rodolfo Romero takes off his glasses and rubs his eyelids, as if to polish a clouded image or, simply, to look within himself and clarify, within the refuge of his memory, what he experienced alongside those who fought with him.

The first and last image that comes to his mind cannot be any other than that of Ernesto Guevara, whom he met one night of an "intense light of full moon and a silence of the tomb," in the threatened Guatemala of Jacobo Arbenz. In those years of military coups and popular opposition, exiles from everywhere came knocking on the door of this Central American country:

"It was June 24, 1954 and Guatemala City had just been terribly bombed. Che arrived at the house of the Augusto César Sandino youth brigade, of which I was the leader, with a letter from a Chilean communist. He asked for Edelberto Torres, another Nicaraguan exile and the son of an eminent anti-Somoza fighter. "As Edelberto was in a meeting of the Party, I asked him to come in and wait. Around two in the morning, when the guards changed shift, he asked me if he could participate in the relief. I didn’t really know who he was, and the responsibility of giving such a task to a stranger made me hesitate, but the letter that he carried with him ended up convincing me.

"Without much ceremony, because in wartime everything is pressured, I gave him a Czech carbine from the guard going off duty who, incidentally, was not Guatemalan, but the Cuban Jorge Risquet Valdés. "And how does one handle this?" he exclaimed when he had it in his hands. In the dark and in a hurry, it was me who gave him some lessons about handling it."

In that meeting with Che, you not only met the revolutionary who voluntarily, without knowing how to use a weapon, would risk doing guard duty with it. You also discovered the romantic man, who loved the poetry of Darío.

"Yes, the night we met, when I told him that I was Nicaraguan, he became very enthusiastic and began to talk to me about Rubén Darío, how much he admired his works, and his desire to read everything that he wrote some day. We didn’t talk for more than an hour, but in that brief time I was able to confirm his great humanity. The next day we said goodbye and I didn’t see him again for a while.

When they gave Arbenz the ultimatum, I went underground, and the Communist Party ordered me to contact all the exiles in the embassies. Dressed in a burlap sack and barefoot, looking like a charcoal vendor, I began to make the rounds of the diplomatic headquarters, and I met Che in the Argentine one. Rapidly, we made arrangements for him to move to the Mexican one.

How did a young Nicaraguan come to lead a communist brigade in Guatemala?

The objective of the Nicaraguan exiles was to train ourselves for overthrowing Somoza, while at the same time contributing to the just democracies of other peoples. First, we were receiving military training in Costa Rica, but pressure from the CIA and the OAS forced us to leave there for Guatemala, at the end of 1948. Incidentally, it was a Cuban airplane that took us.

Immediately I made contact with the communist forces in this country; I even took part in the founding Congress of its party. Activist life in Guatemala shaped my development: I read a lot, studied Marxism, I understood the essence of imperialism and class struggle.

My involvement with nation became great, but I never lost sight of my real cause that was awaiting me in Nicaragua.

Also around this time you knew about the similarities between the dictatorships that oppressed the Cuban and Nicaraguan peoples. How was your first meeting with the leadership of our Revolution?

At that time, the Guatemalan Communist Party gave us the task of collecting signatures in support of a call from Stockholm to convene a peace conference. Whoever collected the most signatures would receive the prize of traveling to the International Conference for the Rights of Youth, in Vienna. In less than 10 days I had collected 1,000 signatures, and off I went.

One day, we Nicaraguans and Cubans sat down to exchange experiences about Somoza and Batista, and it was there that I met Raúl Castro, who expounded to us his certainty that dictators could only be defeated by bullets.

With the passing of time, I kept fully up to date with what was happening in Cuba; in order to inform myself, I tuned in to Radio Rebelde.

Did it surprise you that, a few months after the triumph of 1959, Che sent for you?

No it didn’t surprise me, I knew that Che knew my ideas and my revolutionary development, and that for both reasons he had thought of me.

When I arrived in Havana, after a long interview, I put on the Rebel Army uniform and began to work as a trainee soldier in the Cabaña [Fortress, the Havana headquarters of the Rebel Army].

Some months later I returned to Nicaragua with the objective of restarting the war and it was then when we had our great military setback in Chaparral, on June 24, 1959. The battle was an inferno, it lasted two hours. Nine comrades died and 16 were injured, among them Carlos Fonseca, the leader of our process, who still found the strength to shout, "The youth will not surrender!"

There we were taken prisoner and, through direct moves on the part of the Honduran president, Ramón Villeda Morales—who, without any doubt, was a great admirer of Che—they transferred us to the Cuban Calixto García Hospital, where Carlos’ life was saved.

When we recovered, I joined the Leoncio Vidal regiment of Santa Clara, with Comandante Armando Acosta. Later a group of comrades and I moved on to the Baracoa Artillery School. At that time there were counterrevolutionary uprisings in the Escambray and we were anxious to participate in their eradication with the Cubans. Che proposed it to Fidel, and he told him, "If they want to go, let them."

You have said, in your last meeting with the Argentine with the star in his beret, that there was no exchange of words; however, he did talk with you…

The last time that I saw Che was one midday in 1963, at the Paris customs, and we had a dialogue of hearts, of feelings. He was heading for a meeting and I was going clandestinely to Nicaragua. In Prague, I boarded the same plane on which he had come, but I didn’t know that until we got to the airport. He looked at me with a seriousness that, for others, could be taken as a mute expression. I contemplated him fixedly. We could not exchange words, but we transmitted to each other countless emotions. It was a very moving moment, one of those that are experienced just once in a lifetime.

Once you mentioned that in your travels throughout the world, you had never met a man who, like him, brought together some many virtues. What do you think now, when your journey through life has lengthened a little more?

I maintain the same words as then. There are many brave, honest and principled men, but it is difficult to find all those qualities in one sole person.

Che was so significant for me, that he even taught me not to fear death. Before returning to Nicaragua for the battle of Chaparral, I shook his hand to say goodbye and his question came as unexpected as a bullet:

"And if they kill you?" he said to me.

"You’ll have to bring flowers to my grave," I thought to answer.

"Romero, you have to think that death is a transition toward life," was his brief lesson.

While in our first encounter, it fell to me to give him instructions, on that last opportunity, it was he who revealed an essential piece of knowledge to me. That is why today, clinging to his teaching, and convinced that I have done as much as I could have done, I await death without fear. Moreover, I agree with Sandino; others will guide our cause toward its end.

No comments:

Post a Comment